A Blue-Collar History of Powell River

Our town's story, from the perspective of the workers who built it

“I don't care if we're First Nations people, we're Chinese, we're Japanese, we're German, we're whoever we are, we all need to take pride in our own history. I'm not saying we're the only ones, as First Nations people, that we should be proud of our history. We all should have that.”

Dr. Elsie Paul, Written as I Remember It: Teachings (Ɂəms tɑɁɑw) from the Life of a Sliammon Elder

In August, the Union of BC Indian Chiefs sent a letter to Powell River Council specifically calling our town out for “the deeply troubling trend of Residential School racist denialism” and an “unwillingness to accept historical fact and the work of experts.”1

It’s clear that, as we grapple with the reality of colonialism, our community is going through something of an identity crisis. In a way, it’s understandable. As we learn about the darker side of our past, we're faced with a hard choice: do we shrink in shame, or insist that things weren’t really as bad as they say?

Elsie Paul points us towards another option. Can we hold the fullness of our town’s history without guilt or denial, but with pride? This is my attempt - the story of Powell River from the perspective of the workers who built it.

The Boss’s Town

In 1874, land speculator Robert Rithet purchased Lot 450, a 2,775 acre timber lease on the BC coast. The Tla’amin people who live there were not consulted, and protested the sale and subsequent logging of their land.2 They were ignored, and within a few decades the former village of tiskwat would become the world’s largest newspaper mill.

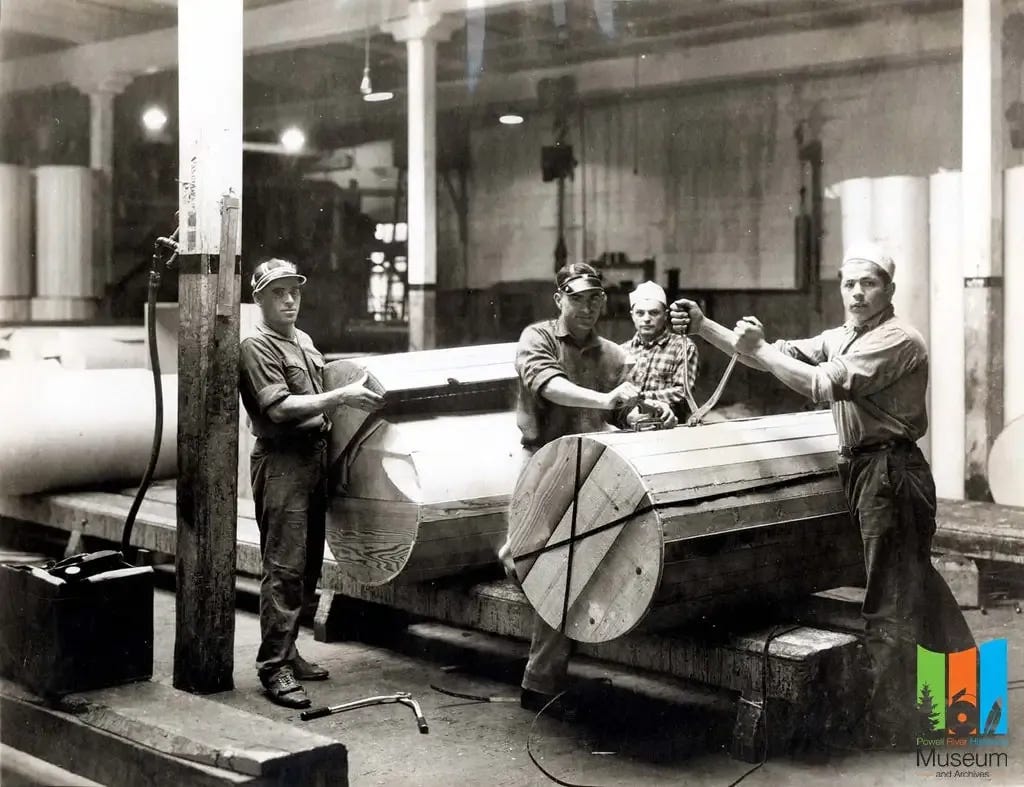

In 1909, having “completely exhausted [the] supply of standing timber”3 at their Minnesota mill, the American businessmen Dwight Brooks, Anson Brooks, and M.J. Scanlon began looking west for new forests to fall. With a seemingly endless supply of old growth, a river for hydropower, and ocean access for easy transportation, they saw the economic potential of Lot 450 and founded the Powell River Paper Company. By April 1912 their new mill was turning out its first rolls of paper, and the beginnings of a townsite was taking form. The newly built employee houses were clean, well constructed, and boasted modern amenities like telephones, plumbing, and cheap electricity. At the edge of green lawns, the streets were boardwalked and tree-lined. There was a community playing field and an asphalt tennis court - all built by the company.

But, despite the company’s benevolence, not everyone was happy. The basic wage for mill work was only 22.5 cents per hour4 ($6.20 per hour in 2024 dollars). Employees were expected to work a physically demanding job for 13 hours straight, six days a week - Sunday was their only day off. Wages trickled back into the company’s pockets every time they paid rent on their company-owned home, or bought groceries at the company-owned store (which was literally called The Company Stores, at the site of the current Townsite market). Isolated and removed from the rest of the province, the company effectively owned and managed nearly every aspect of community life in early Powell River - as one local historian put it, “the entire town was on the company payroll.”5

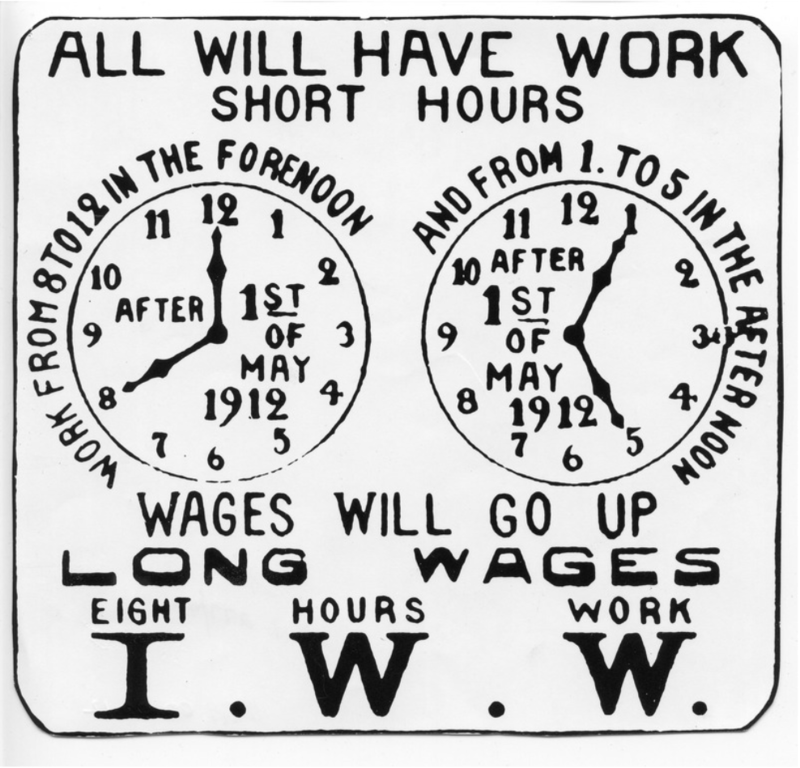

In 1913 there weren’t yet any laws that protected workers’ right to form unions. Regardless, many of the mill workers risked their livelihoods to join the International Brotherhood of Paper Makers and push back against the company rule. Their main objective, in line with a growing international labour movement, was the adoption of an 8 hour work day. The Powell River Paper Company, confident in its power, refused to bargain and locked the union out.

In 1921 union workers, now members of the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulfite and Paper Mill Workers, struck again. This time they wanted company recognition, better wages, and a union shop. In response, the company fired the union workers, brought in strikebreakers from Eastern Canada, and reduced wages by 16%.6

The Mill Loses it Over Ernest Bakewell

Organised labour wouldn’t manage to pose a serious threat to The Powell River Company until the Great Depression shook things up. Tough economic times meant layoffs, dangerous working conditions, and an increased disregard for the environment. There was a growing understanding among workers that the unchecked greed of the rich was to blame for their misery. We must “chop the tentacles off the monster that is leaving a wasted country and a mangled humanity along their roads to profit” wrote an editor of the union magazine, B.C. Lumber Worker.7 Class consciousness was at an all-time high.

It was in these troubled times that Powell River elected Ernest Bakewell, an engineer at the Ocean Falls mill, as their MLA. Bakewell was a member of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), a democratic socialist party that pulled no punches. As the official opposition in the provincial legislature, with 32% of the vote, they openly boasted that “no CCF Government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism.”8

Despite his party’s bold rhetoric, during his tenure in the legislature, Bakewell was an advocate for modest reform. His policies included a reforestation tax on logging companies, government-sponsored salmon habitat restoration, job training for unemployed fishermen, and a transition from clearcutting to selective logging.9

The Powell River Company, facing the prospect of government regulation for the first time, was out for blood. In retaliation, they fired 350 of their employees on suspicion of voting for Bakewell - although an untold number got caught up in the purge for simply being foreign or vaguely left-wing. On top of losing their jobs, the fired workers were booted from their homes, their families blacklisted, and the company even tried to forbid the remaining employees from associating with their old coworkers.10 One old timer remembers how “Giuseppe (Joe) lost his job at the mill in the early 1930s, along with many others, because they said that he had voted for the CCF. He wasn’t a Canadian citizen and had never voted. He was very hurt by this and never forgot it.” 11

There Will Be Blood - the Battles of Ballantyne Pier and Blubber Bay

Emboldened by the election of the CCF into the legislature, new provincial laws that recognised (some) union rights, and general public sympathy - the 1930s saw epic battles across the province as organised labour increasingly threatened employers’ chokehold. Powell River was right at the heart of it.

By 1935 unions had effectively organised nearly every port in BC. Vancouver in particular was headquarter to some of the most militant unions and workers won victory after victory as they struck against the bosses.

Powell River, isolated from the progress of Vancouver unions, was still in the throes of the Great Depression - “about half of the workers there worked only fourteen days a month, the other half eked out an existence by fishing, the odd day’s or hour’s work, relief and loafing.”12 Laid-off employees, desperate for work, accepted contract work at a fraction of their old wages. In solidarity, members of Vancouver waterfront unions snuck into town and, meeting away from prying company eyes, helped fifty-one Powell River dock workers form their first union - The Powell River and District Waterfront Workers Association. When the new union asked management to match their wages with Vancouver dock workers, the company refused and locked them out.

This pissed the unions right off. Longshoremen in Vancouver, Port Alberni, and Seattle refused to unload ships coming from the non-union dock in Powell River. Industry bosses were ready for the fight and retaliated by locking out 900 union dock workers in Vancouver. With protection from armed police escorts, the shipping industry brought in strikebreakers to continue unloading Powell River cargo. 13

On June 18, 1935, over a thousand striking longshoremen and their supporters marched down Vancouver streets toward Ballantyne Pier to “talk to the non-union workers.” But, before they could get to the docks, they were stopped by a wall of baton-wielding police and machine guns aimed directly at them. Undeterred, strike leader Ivan Emery bad-assedly said: "In the war, many of us faced the guns of the German army. Now we are faced with a squad of mounties with machine guns behind them. I believe there are enough returned men among us willing to listen to the rattle of machine gun fire again."14

The battle lasted three hours, saw the first non-military use of tear gas in Canada, and ended in the hospital for many. The legacy of the fight is ambiguous, with no meaningful resolution of tension between workers and bosses.

Texada Island in the 1930s, like Powell River, was under the thumb of a monopoly - the Pacific Lime Company. A mining and mill operation, Pacific Lime owned virtually all of the facilities in Blubber Bay. In 1938, organised under the International Woodworkers of America (IWA), workers struck and took Pacific Lime to court. In legally binding arbitration, Pacific Lime conceded to wage increases and a promise not to fire any union workers. A few weeks later, Pacific Lime fired twenty-three union workers. On June 2, two-thirds of Pacific Lime’s employees walked off the job.

Rather than enforcing their government’s labour laws, the Provincial Police worked hand-in-hand with Pacific Lime to escort non-union workers that the company brought in by steamship from Vancouver. For months, workers picketed and whenever fresh strikebreakers arrived at the Blubber Bay wharf a skirmish would break out between the strikers, company thugs, scabs, and police.

By mid-September tensions boiled over into a full-blown riot. While it’s unclear who started it, eleven strikers ended up in the Powell River hospital and twenty-three were arrested. Among those arrested was local vice-president Robert Gardner who was “taken into a private room and beaten by Constable Andrew Williamson, suffering four broken ribs.”15

The next day, forty members of the Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulfite and Paper Mill Workers travelled over from Powell River and warned police to back down - or else four hundred of them would be back “and we won’t fool with you bastards.”16 While badass, the threat wouldn’t come to anything - after eleven months, the Pacific Lime strikers were worn out. Charged with rioting and unlawful assembly, twelve were sentenced to 4-6 months of hard labour. Gardner was among those convicted and, still weak from his injuries, died while serving his sentence in Oakalla prison.

Despite violent repression and blatant collusion between the police and company bosses, workers didn’t give up the fight and continued to chip away at company power. In 1946 the IWA won a historic victory - a 40-hour work week. In 1958, unionisation in BC peaked at 54% of the workforce. By 1973, 2,233 of 2,600 Powell River mill workers were unionised.

Marxist Catholics?

Like a lot of Powell Riverites, I bank with First Credit Union. As the name suggests, it was the first credit union in BC - founded in 1939 by Father Leo Hobson and Walter Cavanaugh, a chip screen tender at the mill. Cavanaugh, like a lot of mill workers at the time, didn’t qualify for a mortgage from a traditional bank. Undeterred, after researching his options he stumbled onto the idea that a worker-owned credit co-operative was a way that workers like him could bypass the gatekeepers at the traditional banks, and directly finance their own loans and mortgages.

Revealing of the town’s character is how Cavanaugh’s radical and socialist ambition of a worker-owned bank found meaningful support in the community and was nurtured into reality. He found his strongest ally in Father Hobson at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, who agreed to help Cavanaugh in his goal. Hobson’s church soon grew into a meeting place for some 140 workers who helped organise and turn the cooperative vision into reality. The diverse group of Catholics, Protestants, Conservatives, and Socialists all squeezed into the small church to hear Hobson’s class-conscious sermons. Notably, Hobson drew on the Encyclical of Pope Leo XIII Rerum novarum,17 or "Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor” which, amongst other anti-capitalist sentiments, taught that:

“The richer class have many ways of shielding themselves, and stand less in need of help from the State; whereas the mass of the poor have no resources of their own to fall back upon, and must chiefly depend upon the assistance of the State. And it is for this reason that wage-earners, since they mostly belong in the mass of the needy, should be specially cared for and protected by the government”

Conclusion

As time passes, so does our understanding of history. But, as we tear down the old historical myths, we can’t forget to remember our real history. It seems that a lot of us don’t know who we are, and how we got here.

I’ve pointed toward a handful of local historical figures that I feel proud to be connected to, and inspired to continue in their tradition. There’s Father Leo Hobson, a class-conscious preacher, and credit cooperative pioneer; Robert Gardner, a martyred union activist who died at the hands of police in the fight for fair wages; Ernest Bakewell, an unabashed socialist who advocated for labour rights and the environment. There are countless others, and they’re not all white men (it just happens that white men’s stories are well-recorded and easy to find). I hope that we can shine a light on their stories too.

RE: UBCIC Resolution 2024-33 “Rejection of Residential School Denialism” UBCIC. August 12, 2024

Tla’amin History from the Crossroads of Colonialism Colin Osmond, 2018.

Scanlon Mill Closes The Virginia Enterprise. Aug 13, 1909, Page 8

Powell River: The Largest Single Site Newsprint Manufacturer in the World. Barbara Ann Lambert, 2009.

ibid.

ibid. (some good local union history!)

quoted in: A Bridge to Nowhere: British Columbia’s Capitalist Nature and the Carmanah Walbran War in the Woods (1988-1994). James Davey, 2012.

The CCF’s Regina Manifesto July, 1933.

Thirty Seats for B.C. Legislature Proposed in House. Daily Colonist, Feb 29, 1936. Page 8

Rusty Nails and Ration Books. Barbara Ann Lambert, 2002.

Memories of the Mill: A Memoir Anthology. qathet Museum & Archives Society. 2023

Start Small, Dream Big: the 75 year history of BC’s First Credit Union. Linda Wegner, 2014

quoted in: Vancouver's "Red Menace” of 1935: The Waterfront Situation. R. G. McCandless. 1974

On the Line: A History of the British Columbia Labour Movement. Rod Mickleburgh. 2018

ibid.

Wegner, 2014

this is fantastic. Well done.

I think one important take away too that you didn’t highlight is that change is hard, it’s non-linnear, but it is possible.

Things have gotten better in many ways. It’s okay to acknowledge progress, while still holding on to what has yet to change.

I think some of us sometimes cling too tighly to our failures and do not spend enough time honouring the wins that were fought for by those who came before.

These stories of heroic sacrifice and bravery are inspiring for us! They prove that change does happen.

In your story, there was state-collusion with corporations (bad). But there was also the court that supported the union rights! And Church collusion with workers!

Life’s a mess. Change is a mess. Thank you for bravely pointing to a way through the labyrinth. And keeping the torch alive:

We can make a better world!

Very interesting! Thanks for sharing.