Israel Powell's Great Train Robbery

How British Columbia's first Superintendent of Indian Affairs got really really rich

Israel Powell used to be an obscure name in British Columbia’s history. Now he’s the latest historical figure to get dragged through a public reckoning.

In Powell River, a coastal town named in his honour, opinions on Powell’s legacy can bring up some big feelings. His defenders say he’s the victim of a cancel culture smear campaign and that he should be remembered as “an enlightened and liberal administrator with broad sympathy for the Indigenous condition.”1

The cancel culture smear campaign says Powell was “an agent of colonialism who advocated for residential schools and the dismantling of Indigenous culture and governance systems.”2

How do we make sense of these wildly different perspectives?

Meet the Powells

Israel Powell was born in Ontario to a wealthy and powerful family. His dad, Israel Powell Sr. was a shipping magnate and member of the Legislative Assembly. In 1841, he helped unite Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec) into the Province of Canada. But Powell’s real ambition was bigger. He was a Reformer who advocated for separation from Britain and the creation of a new, independent country. Powell would die in 1852, fifteen years before Confederation, but his two sons would carry his torch.

Israel Powell Jr.’s brother, Walker Powell, was Adjutant-General of Canada’s militia from 1862-95. Under Powell, the militia acted as Ottawa’s muscle, expanding its authority westward over lands claimed by the Métis and Indigenous nations. Louis Riel, a lawyer and Métis leader, opposed Ottawa’s incursion and demanded self-government for his people. Ottawa refused. Instead, they sent Powell and his troops west to put down Riel’s Red River Resistance in 1870, and Northwest Resistance in 1885.3 The Métis and their Indigenous allies were outnumbered and outgunned. Riel was hanged in November 1885.

Israel Powell would follow a distinct, but parallel path to his brother’s. After graduating from McGill’s medical school in 1860, he briefly returned home to practice medicine. But he was a young, adventurous guy and was soon pulled west by the allure of the booming Cariboo gold rush. At twenty-six he travelled across the continent to the BC coast. The British Colonist reported on Powell’s arrival in Victoria that he “brings very high testimonials from Canada, which speak in the most favourable terms of him" - including a letter from his dad’s friend, John A. MacDonald.4 Powell would never make it out to the Cariboo gold fields. Instead, within a year of his arrival on the coast, he was elected to the House of Assembly of Vancouver Island.

It’s significant to note that Powell’s election wasn’t democratic in the way we understand the word today. James Douglas, the Governor of British Columbia at the time, was "utterly averse to universal suffrage”5 and only those who owned “20 acres of land or upwards”6 had the legal right to vote. Women and Indigenous people weren’t allowed to buy land, and the average worker couldn’t afford twenty acres - so it was only rich white men who voted Powell into office. He was elected to represent Victoria with 203 votes out of a population of 3,630. 7

Railroad Tycoon

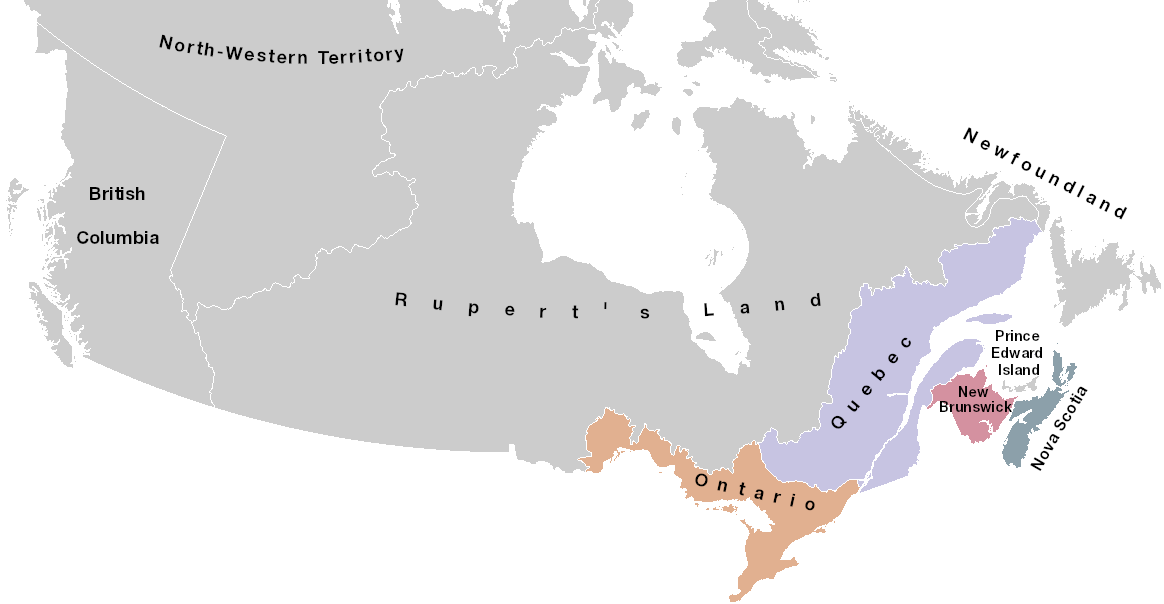

The key to understanding who Israel Powell was, is to place him within the context of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and Canada’s rapid westward expansion. During Powell’s tenure in the Legislature, BC was still a British colony. It was separated from Canada by Rupert’s Land, a massive territory that was British in name only. In reality, it was an Indigenous-governed territory known to Canadians by only a small handful of fur traders, missionaries, and explorers.8

To tempt BC into Confederation, John A. MacDonald (Canada’s first Prime Minister) promised to build a railway across Rupert’s Land within ten years and connect the Pacific coast to the Eastern Provinces. Most people in Victoria were skeptical of MacDonald’s wildly ambitious promise and wary of conceding power to a distant government in Ottawa. Still, Powell continued to champion the idea, an unpopular position that cost him re-election in 1868.9

By 1871 political tides had shifted, and BC joined Canada. In reward for his loyalty, MacDonald appointed Powell as BC’s first Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

Work on the CPR began immediately. Aside from extreme distances and inhospitable terrain, one of the biggest obstacles to construction was that Canada had no legal claim to the Indigenous lands the railway was crossing. It was Powell’s job to help resolve this “Indian problem” and smooth the transfer of land to the Canadian government.

With large sections of the railway completed in the East, it still wasn’t clear what route the railway would take once it arrived at the mountains of BC. As late as 1877, it was thought that Bute Inlet (north of Powell River) was “by far the most advantageous point to touch salt water”10 and the likely choice for the railway’s terminus.

As the CPR worked its way west, it was preceded by a frenzy of real estate speculation. Reserve Commissioner Gilbert Sproat noted that:

“several influential persons in Victoria are interested in land speculations in connection with new discoveries on Texada Island, and a possible railway terminus at Bute Inlet, and they would rather that the Indians, even at this late period in the history of the province were left out in the cold for some time longer.”11

Israel Powell was one of those influential persons. He intervened to delay the survey of Tla’amin territory (Bute to Jervis Inlet) and facilitate the illegal sale of a 2,775-acre timber lease that would later become the city of Powell River.12

Powell Gets Stinking Rich

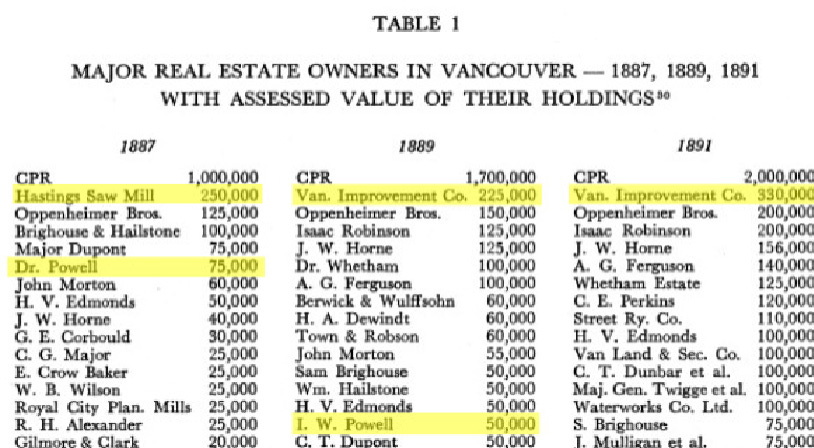

Powell first dipped his toes in real estate speculation at the expense of the Tla’amin people, but he would go whole hog on speculation a few years later when he turned his attention toward Vancouver. In 1869, the Provincial government had confined the Squamish people to a thirty-seven-acre reserve at the mouth of False Creek.13 The rest of their territory was up for grabs and Powell started scooping up properties. First, a share in Vancouver’s Hastings Saw Mill. Then, in 1877, District Lots 182 and 183 (the future neighbourhood of Gastown). Then, through a real estate syndicate he belonged to, another 330 acres along Burrard Inlet.14

Powell knew something that most people didn’t. Until 1884, the public believed Port Moody, twenty kilometers east of Vancouver, was destined to become the railway's Western terminus.15 While Powell was quietly buying up cheap land in Vancouver, Port Moody was going through a real estate explosion.

How did Powell know where the railway would end, years before almost anyone else?

The answer is: because of a greasy dude named Arthur Ross. Ross was a Member of Parliament representing Winnipeg and a freewheeling real estate man. He was briefly one of the richest men in Winnipeg but was left holding the bag when the city’s real estate bubble burst. A local paper called him a swindler engaged “in the wildest schemes of speculation.”16 He arrived in Victoria running from his significant debts, hoping to use his political connections to get another chance at riches before the railway arrived on the Pacific coast.17

Ross had a powerful friend in William Van Horne, president of the CPR. In exchange for Ross’ support of the CPR in Parliament, Van Horne gave Ross an invaluable letter “to the effect that the terminus was to be at Coal Harbour, not Port Moody.”18 Having no money, Ross enticed elite members of Victoria society to join his insider trading scheme. In exchange for his valuable information, they gave him a one-fifth share in their newly formed real estate syndicate - the Vancouver Improvement Company. Its membership included prominent political figures: Major Dupont19, David Oppenheimer, and Israel Powell.

At the last minute, just before the railway was completed in 1885, the Provincial government gave the CPR six thousand acres of free land in Vancouver. The Vancouver Improvement Company gave one-third of their Hastings Mill property.20 Van Horne announced that the ocean at Port Moody was too shallow for the CPR’s ships and Vancouver would become the railway’s terminus instead.

Vancouver property values skyrocketed, and Powell and his friends got extremely rich.

What About Everyone Else?

“This robbing Port Moody of the terminus is beginning to rouse a spirit of rebellion, and all investors are beginning to show very ugly teeth after being assured so many times by the Government that Port Moody was the terminus, invested their little all in clearing out the wilderness and building a home; then for the Government to turn their back on us and allow a syndicate of land grabbing speculators to extend the line to English Bay.”

Port Moody Gazette, August 1, 1885

History books credit Israel Powell with bringing the railway to BC. But, of course, it was workers who built the railway. Chinese workers did the bulk of the labour and were paid poverty wages for the most dangerous jobs. Depending on the source, 600 to 2,200 died during the CPR’s construction and many are still buried in unmarked graves along its tracks.21 White workers made a modest living, but few had access to the wealth, political influence, or insider knowledge necessary to come out on top of the railway-fueled real estate boom. More likely, the average worker simply struggled to afford a home, just like we do today when rich people speculate on land.

As we consider Israel Powell’s legacy, we should remember that he wasn’t a friend to working people. He was born rich, elected into the legislature by rich men, and chose to use his power and influence to accumulate even more riches for himself and his rich friends - at the expense of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Collaboration No More: How the Powell River, B.C. Name-Change Debate Turned Nasty. Frances Widdowson. October 2024.

The Powell in “Powell River” Colin Osmond.

Lt. Col. Israel Wood Powell Lawrence Runnells, 1974

ibid

Sovereignty and the Aboriginal Nations of Rupert's Land. Kent McNeill. 1999

Israel Wood Powell Dictionary of Canadian Biography. John Lutz, 1998

quoted in: The Battle of the Routes Daniel Marshall, 2020

quoted in: Deception, Delays and Theft. The truth about tiskwat you won’t find in history books. Davis McKenzie. October 2023.

ibid

“Sḵwx̱wú7mesh traditional territory is 6,732 square kilometers (673,200 hectares), encompassing 23 villages totaling 28.28 square kilometers (2,828 hectares). These land parcels are scattered from Vancouver to Gibsons Landing and the area north of Howe Sound.” (Squamish Nation)

Early Vancouver Volume Three Major Mathews, 1935

CPR Ends in Vancouver. Leah Siegel 2020

Decades later, in an interview with a city of Vancouver archivist, a member of the Vancouver Improvement Company tells a particularly sketchy story about Arthur Ross:

“One day Van Horne got off the steamer from Tacoma at Victoria and A.W. Ross was with him. A sheriff tapped Ross on the shoulder as soon as he touched the wharf. It was a most awkward situation for Ross; he had come up on the boat with Van Horne and here he was under arrest as soon as he landed. Some clergyman in Australia had entrusted some funds to him for which it was said he had not accounted.”

quoted in: Dictionary of Canadian Biography

Major Dupont had been fired a few years earlier from his job as Ontario’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs when an investigation found that he had stolen over 1,000 acres of Indigenous land at Manitowaning. The Wikwemikong First Nation and the Department of Indian Affairs' Mismanagement of Petroleum Development

Early Vancouver Volume Three Major Mathews, 1935

Chinese Labour on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Asian Heritage Society