The Cowichan Decision

and the sanctity of the Registry

“These are profound issues that are hard to consider in the absence of the real people … the homeowners, the business owners, who will be affected by this decision. I want the court to look into the eyes, metaphorically speaking, of the people who will be directly affected by this decision and understand the impact on certainty for business, for prosperity and for our negotiations with Indigenous people.”

- Premier David Eby, September 2025

In August, the longest trial in Canadian history wrapped up. For nearly five years, dozens of lawyers fought over the rights to eight square kilometers of industrial land on the bank of the Fraser River.

The judge’s decision is long - almost nine hundred pages of dense legalese and debate over historical minutiae. Ultimately, she decided in favour of the Quwuts’un Nation, recognizing their right to their traditional village of Tl’uqtinus. In the process, she declared Canada and Richmond’s title to the land “defective and invalid.” For individual property owners in the area, she found that their title coexists with the Cowichan’s.

It’s the first time a BC court has acknowledged that Aboriginal title and fee simple title can coexist.

It’s a groundbreaking ruling. For the non-lawyers, fee simple is private property. Aboriginal title is a right to the land which, when recognised, acknowledges an Indigenous group’s “right to possess the land; the right to economic benefits from the land; and the right to proactively use and manage the land.”

Some people are stoked on a big win for Indigenous rights. Others are pissed. They don’t want their private property coexisting with Aboriginal title. Most people, it seems, are simply confused about the ruling and unsure if, or how, it will impact their lives.

Fundamentally, the Cowichan decision challenges our understanding of land.

the land question

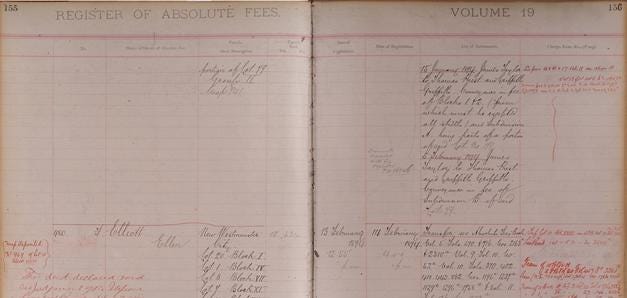

A lot has happened to Tl’uqtinus since it was sold in 1871.

The guy who first bought a piece of the village was Richard Moody, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works for the Colony of British Columbia. It was a shady sale. As Commissioner, he was supposed to establish reserves around Indigenous villages to protect them from land speculators. Instead, he decided to land speculate himself. To quote the judge,

“Moody acted in his own self-interest and contrary to Douglas’ express directions and colonial policy, taking appropriated Indian settlement lands for himself.1 He did so covertly, through a land agent. His failure to take steps to stake out an Indian reserve at the Cowichan’s village resulted in a personal benefit to him — the acquisition of part of the Cowichan’s waterfront land at Tl’uqtinus. As the plaintiffs put it, the very Crown official clothed with the task and responsibility of protecting the settlements of the Indigenous inhabitants, surreptitiously took part of the Lands of Tl’uqtinus for himself.”

The village has long since been subdivided and parcelled out. Gone are the longhouses, blueberry fields, eulachon, and freshwater streams that once defined the area.2 In their place stands an Amazon Fulfillment Center, a Coca-Cola bottling facility, a golf course, and forty-five privately owned homes.

It’s a big deal that the Cowichan were able to get their village back after such significant private development. For over a century, the Province has acted as if Aboriginal title vanishes the moment the land is sold to a private owner.

What the Cowichan decision recognises is - private property doesn’t erase Aboriginal title and hasn’t since 1763, when King George III proclaimed that all land in North America is Aboriginal land until ceded by treaty. BC has been breaking the law for a long ass time. Check out this newspaper article from 1877:

“First and foremost, there is a question of the unextinguished Indian Title in the soil…. It would cost a great sum of money to extinguish the Indian title here…. The practical difficulties in settling this question are so great that it has not been raised at present…. But what guarantee can there be that the Indians themselves will not raise it at some future, perhaps not distant, time?”

British Columbia’s problem of “unextinguished Indian Title” has been kicked down the road for generations. Now, the fate of millions of dollars of real estate in the industrial heart of the Lower Mainland is on the line.

The chickens have come home to roost.

Complicating things, there are a lot of people with a lot of power who have a lot of money tied up in real estate. They don’t like to see their investments threatened.

They’re sounding the alarm. Corporate media is on a tear, publishing opinion pieces with incredible headlines like: “First Nations have said they don’t want to seize homes ... but they conceivably could.” Social media is thick with untruths. It’s important to note that, despite claims to the contrary, the court’s decision doesn’t invalidate any private homeowners’ title. Only lands owned by Canada and Richmond have been returned to the Cowichan.

Still, Indigenous rights are creeping close to BC’s favourite investment vehicle. It’s got homeowners and investors nervous. Who will compensate them if the unthinkable happens, and their property values decline?

the foundation of our democracy

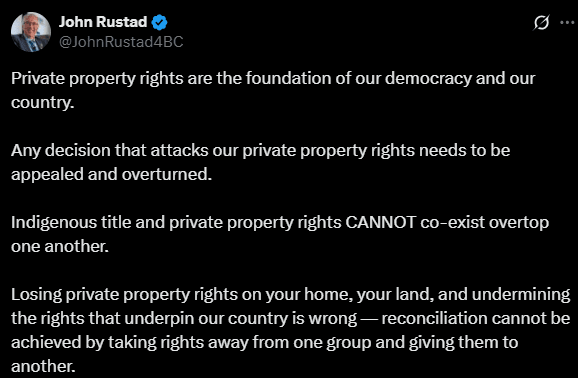

The Cowichan decision has politicians tearing off their orange shirts and scrambling over to team private property.

On one end of the spectrum, there’s Vancouver MLA Dallas Brodie, who posted a video to social media that calls the decision “nothing more than a brazen land grab by Indigenous people, ripping apart the very fabric of British Columbia as we know it.” Leader of the Opposition, John Rustad, is warning that “property values are at risk… and investors will start running, not walking, out of British Columbia.”

But even the NDP, once proud champions of reconciliation, are hard backpedaling. They “disagree strongly with the decision,” and are “committed to protecting and upholding private property rights.” Instead of negotiating in good faith with the Cowichan, as the judge ordered, they’re lawyering up and appealing the decision.

There’s one guy in particular who’s been riling up the propertied class. That’s Malcolm Brodie, former lawyer and current mayor of Richmond. Shortly after the decision was released, his office sent letters to private property owners in the newly declared Cowichan Title Lands.

It grumbles that the Cowichan’s title was granted “over lands that the plaintiff’s ancestors had abandoned roughly 150 years in the past.” It blasts Canada and the Province (Richmond’s co-defendants) for not backing the city in its argument for extinguishment, an outdated legal concept that’s been consistently rejected by the courts for over thirty years. It blames the Cowichan for not warning private landowners that their title may be “negatively affected” by a recognition of their Aboriginal title (something Richmond didn’t do either). For good measure, Brodie also tagged on an op-ed by Robin Junger, former Deputy Minister of Energy, Mines & Petroleum Resources.3

The Cowichan Tribes responded to Brodie’s letter, saying his “statements are, at best, misleading, and at worst, deliberately inflammatory.” The Union of BC Indian Chiefs chimed in, saying that “framing this decision as a threat to private property stokes fear and unfairly scapegoats First Nations.”

Still, with elected leaders of all stripes rejecting the court’s ruling, it’s hard to know what to think. After all, the overwhelming majority of the province is unceded and potentially open to similar Aboriginal title claims. Is private property at risk? Has reconciliation gone too far?

I’m focusing on Malcom Brodie’s letter because, buried in the muck, is a key to understanding what all the fuss is about:

“The court’s decision… to dismiss arguments based on the Land Title Act and the sanctity of the Registry under British Columbia’s Torrens system, introduces enormous uncertainty into the security of any title in British Columbia.”

the sanctity of the Registry

SANC’TITY, noun

Holiness; state of being sacred or holy.

Goodness; purity; godliness; as the sanctity of love

- Webster’s Dictionary

“All clues point to young Torrens inventing the new system of land registration, which now bears his name, in order to complete the dispossession of the Aboriginal people.”

- Dr. Sarah Keenan, legal scholar at the University of London

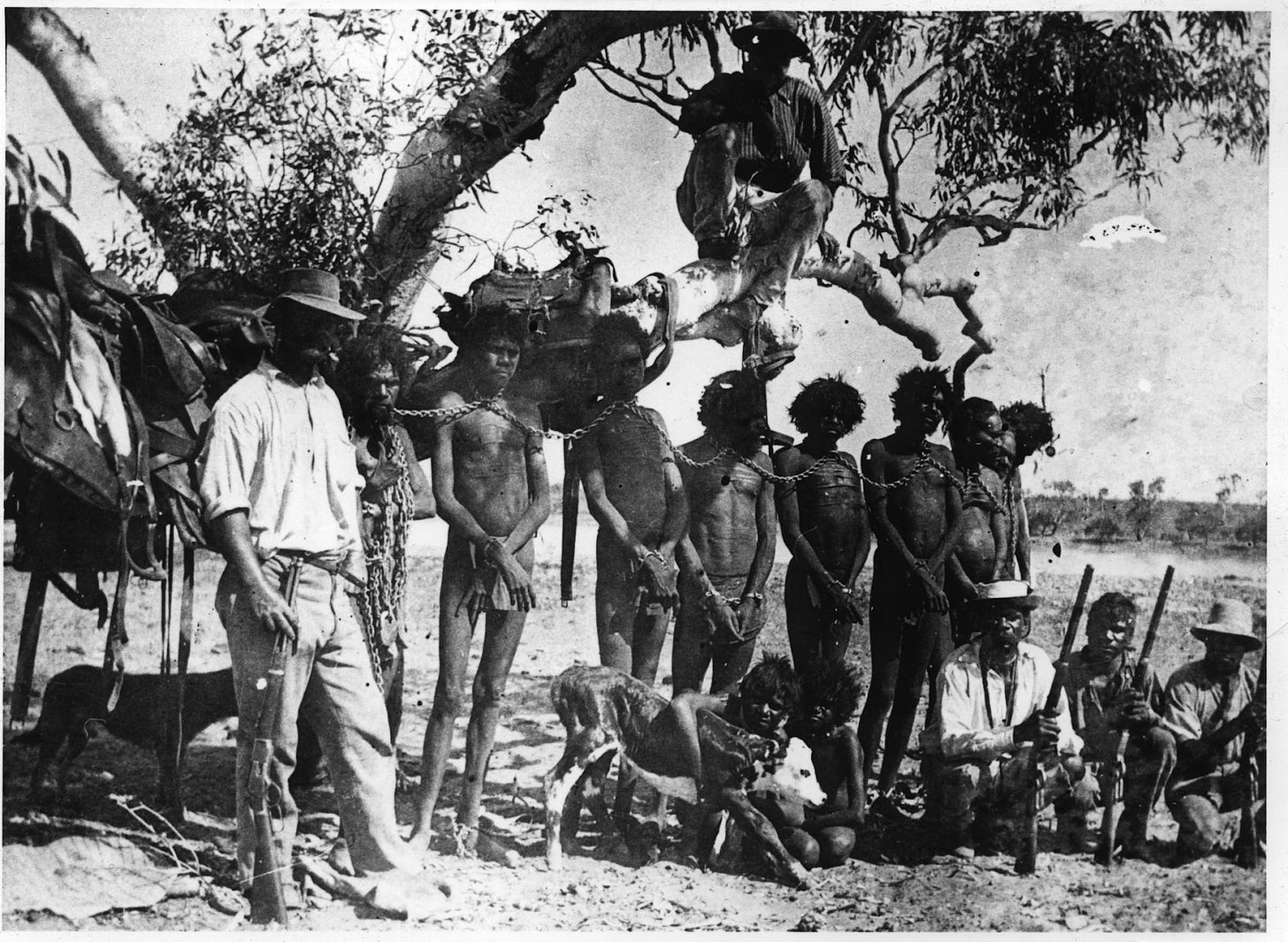

The Torrens system is how land ownership is managed in BC. It’s named after Robert Torrens, an English bureaucrat who invented the system in 1858 to simplify land sales in the new colony of South Australia.

Before the Torrens system, South Australia, like British Columbia, used a deeds registration system to manage property ownership. Every time a property was sold, the title had to be painstakingly proved by tracing the chain of ownership back to its original owner. It was slow, expensive, and there was no guarantee of the title’s validity.

A big problem for early settlers in the colonies of South Australia and British Columbia was that most of the land had not been surrendered by treaty. The historic-minded deeds system validated Indigenous claims to the land and cock-blocked the Europeans who wanted to buy it. As John Helmcken (Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island) said in 1860, we must “quiet the Indian claim to lands in this Colony… no doubt ought to exist in the mind of any person, whether or not he can occupy the land he buys; and so long as there is doubt people will not buy.”

That’s where Torrens’ new system came in clutch. Instead of relying on a cumbersome chain of title to prove ownership, the colonial government created and controlled a new, written land registry. Through a legal sleight of hand, historic claims to the land were erased. Now, if your name is in the registry, you own the land. It’s simple, effective, and clean.

The system gave investors the confidence they needed to stake their claim to land on unceded Indigenous territories. As the new legal regime spread across the British Empire, colonies boomed with a speculative fever. Fortunes were made wheeling and dealing real estate in the freshly opened markets – Irish estates bankrupted by the Potato Famine, rubber plantations in Malaya, sheep pasture in South Australia – the world was for sale.

In 1870, the Colony of British Columbia joined the frenzy and adopted the Torrens system. One year later, Moody bought his property on the Quw’utsun village of Tl’uqtinus.

what’s sacred about land?

“For Indigenous Peoples, our Aboriginal Title and connection to the Land is certain, it is in the bones of our grandmothers buried in the earth, and in the blood which beats in our hearts”

- Union of BC Indian Chiefs, 1998.

Malcolm Brodie is absolutely spot on that the Cowichan decision has fouled the sanctity of the Torrens system.

But Aboriginal title is hardly the first, or only thing to violate a private owner’s right to their land.

For example, you don’t own the subsurface rights to your property in BC. Mining companies have the right to force you from your home and strip mine your land. The same goes for oil and gas. The government regularly expropriates land from private owners to build highways, roads, and public works. Municipal bylaws limit how tall we can let the grass grow on our own lawn.

So, why are people freaking out over the threat of Aboriginal title, but meekly accept the limits of our current, partial claim to ownership?

By naming the Torrens system, Malcom Brodie hints at an answer. What’s sacred, what’s foundational to our democracy and country, what fires up the people who have money and power - isn’t the land itself, or the inviolability of our homes, but the right to accumulate profit from owning land.

Aboriginal title challenges that.

It’s a legal right that exists outside of the speculative tradition. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal People found that Aboriginal title doesn’t include “the right to alienate or sell land to outsiders, to destroy or diminish lands or resources, or to appropriate lands or resources for private gain without regard to reciprocal obligations.” The Union of BC Indian Chiefs agrees, saying that Aboriginal title “prevents Indigenous Peoples from viewing the Land as a commodity to be bought, sold or traded.”

The naysayers aren’t wrong - by recognising the existence of Aboriginal title on private property, the Cowichan decision presents a challenge to land ownership as we understand it in British Columbia. Specifically, it asks us to consider values other than the accumulation of private wealth.

For some people, that's a scary idea.

James Douglas, governor of the Colony of British Columbia

Today, Fraser River eulachon stocks are in a state of significant decline (around 99% below pre-colonial levels) with a spawning biomass under 10 tonnes. Pre-colonial estimates suggest spawning biomass runs of 1000-2000 tonnes were the baseline.

Wow and thank you, Craig. You have written/given the best overview of the recent Cowichan Decision. Recently, a retired neighbour and I were talking. She was up-in-arms citing misinformation, thinking her property rights are threatened. But you explaining that mineral rights (subsurface rights) under our properties, as well government regularly expropriates private property lands, like your example of Site C Dam, is spot on. Which makes me wonder: Are the statements said or read at public meetings about "unceeded lands" sincere or just lip service to make non-Aboriginal people acknowledge feel good about past actions? Am I wrong?

Thank you for doing REAL research on this topic. The amount of misinformation, and immediately showing peoples true racist colours has been frankly disturbing.