The Crofton Mill Closure

China’s fibre grab and a century of capital flight

For decades, the Crofton Mill has been the beating heart of North Cowichan’s economy. Each year, it contributed around five million dollars in property taxes and good-paying union jobs to over three hundred and fifty workers.

Unfortunately, the gravy train has run dry. In December, Domtar (the company that owns the mill) announced its plan to permanently close, citing a “lack of access to affordable fiber.” Tuesday will be the mill’s last day.

Crofton isn’t the only mill town going through hard times. Grand Forks, Vanderhoof, 100 Mile House, Prince George, Chetwynd, Houston, Fort St. John, Mackenzie, and my own town of Powell River have all lost their mills in the past few years.

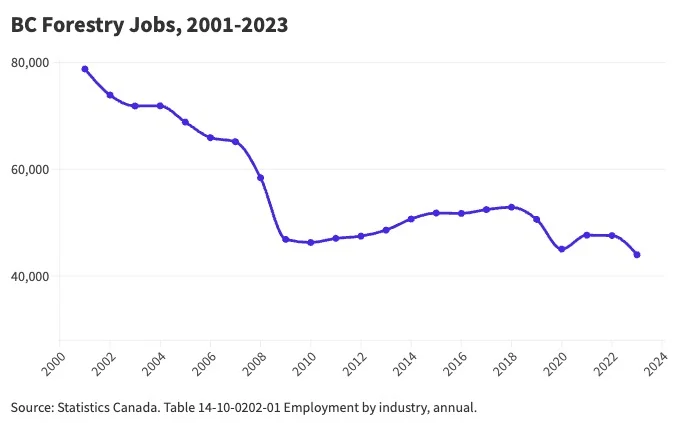

Clearly, British Columbia’s forest industry isn’t doing so hot. The question is,

why are all the mills closing?

After Domtar’s announcement, Aaron Gunn, MP for North Island—Powell River, was quick to point his finger at the NDP and environmentalists, saying:

“This decision is the result not of general economic conditions, but of specific government policies. In particular, a series of anti-forestry, activist-driven policies implemented by the NDP that have restricted access to an economic and predictable supply of fibre.”

Earlier in the year, Gunn and a handful of coastal politicians1 travelled to Victoria to offer their solution to the crisis. In an open letter to David Eby, they wrote:

“We need urgent leadership to cut red tape, restore investor confidence, and ensure our world-class forestry workers can continue providing for their families… Government needs to streamline permitting, restore legal and regulatory certainty, abandon ideological, one-size-fits-all land-use frameworks like 30×30, and support a predictable fibre supply so Canadians can get back to work.”

Domtar’s annual report to the US Securities and Exchange Commission mirrors what the Conservatives have been saying.

It warns that in the future, they “may have difficulty obtaining wood fiber at favorable prices, or at all.” It lists “environmental litigation and regulatory developments, activist campaigns and litigation advanced by Indigenous groups” as its main obstacles.

Ravi Parmar, the NDP’s Minister of Forests during the industry’s collapse, is in a tough spot. Facing calls for his resignation, he’s thrown a word salad at the wall, hoping something will stick. He names “volatile markets, low pulp prices, shrinking fibre, climate-driven wildfires, conservation measures and punishing Trump duties and tariffs” as reasons for the Crofton Mill closure.

Somehow – while everyone else is getting dirty tossing around blame – the owner of the Crofton Mill, Indonesian multi-billionaire pulp and paper scion Jackson Wijaya, has managed to stay conspicuously clean.

why isn’t anyone talking about Jackson Wijaya?

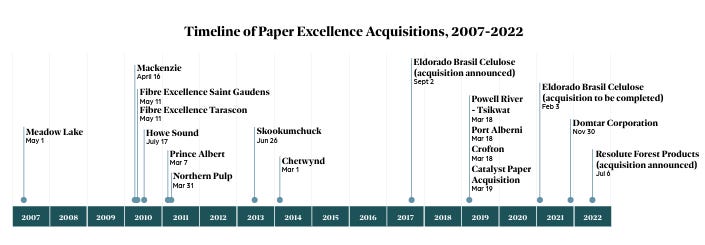

In 2006, twenty-six-year-old Jackson Wijaya founded Paper Excellence (renamed Domtar in 2024) with the purchase of the Meadow Lake Mill in Saskatchewan. Within a decade, he’d expanded his empire to include six pulp mills in BC, two in France, one in Brazil, and a corporate office in Richmond.

But Wijaya was just getting started. His most recent rise in the pulp industry can only be described as meteoric. In three years, he bought Catalyst Paper (2019), Domtar (2021), and Resolute Forest Products (2022) - making him the largest private forest manager in Canada. With permission from every level of government, he now owns dozens of mills and controls over 22 million hectares of Canadian forest, an area seven times the size of Vancouver Island.

For years, there’s been speculation that Wijaya’s money, and the real control of his company, comes from Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) - a subsidiary of his daddy’s business, the multinational conglomerate Sinar Mas.

It’s been hard to prove. Neither APP nor Domtar are publicly listed, and their corporate structures are a maze of numbered companies and offshore accounts. In 2023, a year-long investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists found evidence linking Domtar to APP and the Chinese state-owned China Development Bank. In response, Parliament invited Wijaya to appear before the Standing Committee on Natural Resources to clarify his corporate structure and aims in Canada. Wijaya declined to appear, but issued a weak sauce statement insisting that “Paper Excellence is separate and entirely independent from APP.”

He didn’t stick to the bit for long. In 2024, Wijaya went – psych! – and replaced his dad as the sole owner of Asia Pulp and Paper. With the once blurry lines between his two companies fully erased, Wijaya is now the undisputed GOAT of a global half-trillion-dollar pulp and paper industry.

The problem is (for Canada), Asia Pulp and Paper’s reputation is trash.

It’s been called a “notorious rainforest destroyer,” and “the worst of the worst.” And it’s not just tree-huggers and hippies talking shit. Citing “substantial, publicly available information that APP was involved in destructive forestry practices,” the Forest Stewardship Council – an international body that regulates sustainable forestry – disassociated from APP and revoked its certification back in 2007. Despite repeated attempts to repeal the decision, APP remains uncertified. Even famously evil guys like Nestlé and Walmart refuse to do business with them.

Yet, somehow, without anyone seeming to notice or care, they’ve taken over Canada’s pulp and paper industry.

the fibre grab

Lobbyists on Wijaya’s payroll met with BC officials fifty-five times last year. Their disclosure statements always say the same vague thing - they’re discussing “solutions targeted toward solving for general forestry sector issues, tenure, and fibre supply challenges.”

Whatever it is they’re whispering in officials’ ears, it seems to be working. Domtar has received millions of dollars in public funds, including an $18.8 million grant that was intended to help retool the Crofton Mill and transition it to producing water resistant paper packaging and cutlery. The Parliamentary Secretary for Forests bragged,

“This investment in the mill at Crofton is exciting. Not only will it put people back to work, it is an example of how investment in our forestry infrastructure can help reduce emissions, encourage innovations, reduce waste and make sure we get the most value from every tree harvested.”

Embarrassingly, that’s not what happened. Instead, five months later, Wijaya laid off 100 workers, curtailed operations, and the government had to fight to get its money back.

It’s kind of weird. Who turns down $18.8 million? Other things are hard to understand. Like, why did Wijaya buy the Crofton mill in the first place, if he was just going to shut it down a few years later? Why did he do the same thing in my town? 2

Asia Pulp and Paper’s corporate vision statement offers the best clue I can find. It states, plainly, that their goal is to become the “world’s premier fully-integrated sustainable forestry, pulp and paper conglomerate.”

Integration is the clue. It’s a concept that traces back to Gilded Age industrialists like Carnegie and Rockefeller, who built massive empires based on a single resource (steel and oil, respectively). Their innovation was to harness the power of consolidation. Buy up the competition, squeeze the margins, and concentrate as much of the supply chain as possible under the control of a single owner.

Wijaya’s buying up and shutting down of mills in BC, seen from the perspective of integrating supply chains and stomping out competition, starts to make a bit more sense.

For the most part, Wijaya has been buying up mills that produce northern bleached softwood kraft pulp (NBSK). It’s a long-fibre pulp produced by northern conifers, and an essential ingredient in making quality paper. And buddy, does Canada have conifers. We make more NBSK than anyone else, producing one-third of the world’s supply.

APP, on the other hand, doesn’t produce NBSK. Based in Indonesia and China, their plantations are mostly fast-growing tropical trees that produce a short-fibre pulp which doesn’t have much tensile strength (grippy power) until it’s mixed with long-fibre pulp.

So, until Wijaya started buying up BC forests, APP had to compete on the open market to buy our pulp. And they buy a lot of it. Last year, three-quarters of BC’s pulp and over half of its raw logs were exported to Indonesia and China.

APP wants our fibre. But that doesn’t mean they want our mills. After all, they’re expensive as hell to run. Unionised Canadian mill workers are some of the highest-paid blue-collar workers in the world - the average employee at the Crofton Mill was pulling in over $100k a year.

Without straying too far into the realm of speculation, it’s a safe bet that APP would rather be processing fibre in their Chinese or Indonesian mills, where labour is cheap. There isn’t much reason for them to support British Columbian jobs or the communities that depend on them, let alone esoteric concerns like the environment.

Their expansion into BC is plain old-fashioned extractivism, what whistleblowers have called a “fibre grab”.

PART TWO

how BC handed its forests over on a silver platter

“An epoch, sir, is drawing to a close, the epoch of reckless devastation of the natural resources with which we, the people of this fair young Province, have been endowed by Providence—those magnificent resources of which the members of this Government and this Assembly are but temporary trustees. That rugged, rudimentary phase of pioneer activity is doomed to end.”

- MLA William Roderick Ross, in a speech to the Legislature, January 1912

In its earliest days, logging in BC was a free-for-all. There was little regulation, and the government sold timber leases for pennies an acre. Logging towns rose and fell in an endless cycle of boom and bust.

It was a bad system, and people started getting pissed. We must “chop the tentacles off the monster that is leaving a wasted country and a mangled humanity along their roads to profit,” wrote the union magazine BC Lumber Worker at the height of the Great Depression.

By the end of the Second World War, eight million hectares (mostly on the coast) had been clear-cut and left unplanted. The Province was ready to intervene and appointed Gordon Sloan to lead a two-year investigation - the first Royal Commission on Forest Resources. Sloan’s report laid the foundation of our modern tenure-based forestry system.

It proposed giving private companies long-term, exclusive tenure over Crown lands. Crucially, in deciding who would get access to timber, Sloan was a bigger-is-better kind of guy. He thought that big companies were better capitalised to sustain BC’s remote mill towns. As he said,

“In award of management licences, first priority must be given therefore, in my opinion, to the pulp and paper industries and other large conversion units, especially the great integrated organizations.”

Strangely, he wasn’t worried about the disappearance of old-growth forests, something that was already well underway. Opposite, actually. He thought it was a good thing:

“The vast extent of our productive Coast acreage now occupied by mature and overmature timber illustrates the unbalance of our forest resources. These virgin forests are static and making no net growth and must be replaced by growing trees if we are to progress to within any reasonable distance of the ideal or normal forest cover.”

Sloan’s system of liquidating old-growth worked - for a while. Those old trees were worth a fortune, and for a moment in the mid-1970s, the coastal mill towns of Powell River and Port Alberni had two of the highest per-capita incomes in the entire country.

But old-growth forests don’t last forever, and cracks were starting to show in the foundation. In 1976, Peter Pearse, a forestry professor at UBC, headed a third Royal Commission on Forest Resources. He recognised that the allowable annual cut was set way too high, but the getting was too good. So he put the problem off to the future, saying:

“Allowable cuts should not be set immediately at long-term sustainable levels, but should take advantage of the higher harvest rates possible in high volume old-growth forests.”

To fast-forward a few decades, the Province has stuck to Sloan’s strategy – encourage giant corporations to liquidate old-growth forests – for nearly a century. Unfortunately, it wasn’t a realistic long-term plan.

A recently leaked report found that “throughout the province we’re cutting almost at twice the rate of what is considered sustainable… We’re running out of wood.” Take a look at a satellite map, or out the window next time you fly - it’s hard not to notice.

Making things worse, corporate consolidation has snowballed beyond anything Sloan could have imagined. By the 1990s, fifteen companies controlled half of the province’s forest tenures. Today, it’s just five companies (one of which is Domtar / Asia Pulp and Paper). They have the Province’s balls in a vice.

there was another path

“The newly inaugurated system of ‘Management Licenses’ is patently inadequate. Its end result can only be the concentration into the hands of a few large corporations the entire forest resources of the province”

- MLA Robert Strachan, carpenter and one-time Powell River boy, testifying at the second Royal Commission on Forest Resources, 1957.

Sloan’s recommendations only passed into law by the narrowest of margins.

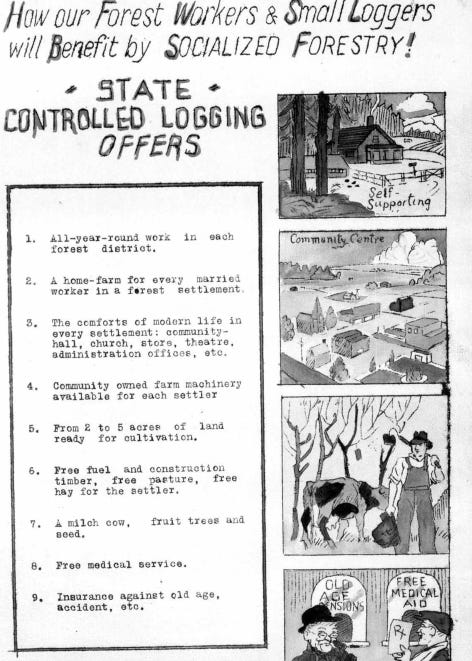

The socialist Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) had a radically different vision for BC’s forest industry. Their goal was to “eradicate capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning.” This was Tommy Douglas’ party, the reason we have universal healthcare, and they came within spitting distance of forming government in BC.

In the 1941 provincial election, the CCF won the popular vote but narrowly lost to the Liberals. In 1945, they won the popular vote by an even wider margin and would have formed government if the Liberals and Conservatives hadn’t formed a coalition to keep them out of office.

Colin Cameron, MLA for Comox and the CCF’s forestry critic, testified at Sloan’s first Royal Commission in 1945. He saw private companies destroying public forests, and a few men getting rich. He wanted to expropriate forest tenures from the private companies and transfer control to the public. In his words,

“My party believes that all the requirements of sound forest policy - social, economic, technological - can be satisfied only through establishment of a public agency, charged with the planting, nurture, harvest, and sale of our raw forest crop. Under that proposal all forest lands and rights would be transferred step by step, from the Crown and private owners to a Crown-owned corporation, to be known as the B.C. Forest Commission… Our goal is the establishment of a distinct forestry system in British Columbia which would eventually absorb all the timber lands of the Province.”

The CCF maintained its position in Sloan’s second Royal Commission on Forest Resources in 1957. Unfortunately — because of the Red Scare, corporate lobbying, capitalist propaganda, all the usual suspects — the CCF’s vision for a Crown-owned Forest Commission was slowly watered down and eventually forgotten.

Today, we’ve come so far down the path of handing our forests over to massive corporations that it’s hard to imagine anything else. But, if we’re going to salvage our forest industry, expropriating tenure from foreign-backed multi-billionaires like Jackson Wijaya seems like a pretty good place to start.

I got a little sloppy citing my sources in this historical section. If you’re a nerd and want to dig deeper, most of what I learned was gleaned from these two papers: The Pearse Commission and the Industrial Organization of the British Columbia Forest Industry (1979) and Sustaining sustained yield: class, politics, and post-war forest regulation in British Columbia (2007).

Including Powell River’s mayor, Ron Woznow. Fun fact: Woznow was the environment vice-president for Fletcher Challenge Canada, a New Zealand based company, during the time that they owned and managed the Crofton Mill (from 1987 to 2000).

Wijaya bought the Powell River mill in 2019 and shut it down in 2021

a great explainer on the Crofton Mill Closure by the Boundary Forest Watershed Stewardship Society came out today: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ydLerj063I

Very interesting article, especially the fact that foreign owned corporations such as Jackson Wijaya’s Paper Excellence are buying up mills and closing them to prevent competition. Time to buy them back and make them crown corporations as per the CCF’s recommendations.