The Westview Ratepayers

and a history of homelessness in Powell River

“Please give a damn about our town and not bring in another of these buildings. These people will never work, they have never tried to clean up. We do not have the facilities to help them find a healing and we can not sustain the amount they are damaging this town, with their actions and habits. The current one is NOT working. A second one would be even worse.”

- September 2024 letter to mayor and council

In the spring of 2023, BC Housing conducted a homeless count in Powell River. Over the course of twenty-four hours, they identified one hundred and twenty-six people who didn’t have a place of their own to sleep at night.

For a small town, that’s a lot of people.

And that’s just people who are obviously homeless. It doesn’t include the “invisible” homeless - people who sleep in their cars, stealth camp in the bushes, or couchsurf with friends. Not to mention the growing number of people who work, but fork out the majority of their pay to a landlord each month, leaving barely enough for groceries. By every measure, times are tough. Visits to the local food bank have doubled since 2019. Crime in the regional district is up thirty-three percent, and violent offences have nearly doubled since 2014.

But we don’t need stats to know there’s a problem. It’s the question of what to do about it that’s divided the town.

shelter problems

In 2021, Lift Community Services (a local non-profit) received funding from BC Housing to set up an emergency shelter on the commercial stretch of Joyce Avenue.

Lift operated the shelter until March 2025, when new owners of the building declined to renew their lease, forcing Powell River’s only emergency shelter to close its doors indefinitely. With nowhere else to go, the building’s former residents migrated to a park next to Lift’s supportive housing building, one of the few places in town still providing homeless services.

Suddenly, for the first time in a long time, Powell River had a homeless camp. It didn’t take long before open drug use, out-of-control campfires, and a proliferation of sketchy-looking dudes started to freak people out.

As one landlord, who owns a five-bedroom home in the neighbourhood, wrote in a letter to city council:

“Despite literally tens of thousands of dollars in upgrades, we have yet to rent to anyone but ‘new comers’ from other cities and provinces. We have been unable to sustain a long-term tenant, and though we keep our home immaculate and securely monitored, we’ve been informed it is ‘too close to the drug house.’ Even when we were connected with a qathet staff member responsible for arranging temporary housing for health care workers during COVID, we were ultimately rejected due to location… The result has been recurrent, persistent vacancies and a significant financial burden. Overall, this may appear inconsequential to the community, and yet I urge you to consider how disturbing it is that we cannot consistently rent a large, clean, well-serviced, well-priced unit when so many indicate a struggle to find housing. Any further development anywhere within the current hospital area will be catastrophic to property values, safety, and the sense of community.”

In response to the growing housing crisis, the Province has proposed the rapid development of two new projects. One is a supportive housing building and emergency shelter on the hospital grounds, near the current homeless camp. The other is a forty-bed shelter and overdose prevention site that will be built on city property next to the Town Centre Mall.

But not everyone’s happy about the plan. Not long after the announcement, a petition circulated, and dozens of people wrote to city council voicing their opposition. The consensus is that supportive housing will “bring more street crime,” and that drug users “being provided with a home by the taxpayers is not a right if they disrupt the neighbourhood.”

westview ratepayers’ society

“We believe that any new building should be located in a different area of the City”

-Westview Ratepayers Society position on BC Housing’s supportive housing proposal, September 2024.

The most organised voice to emerge in opposition to the proposals has been the Westview Ratepayers’ Society. Boasting an all-star roster of local political heavyweights, it was formed to represent the interests of property and business owners during the early days of the pandemic. Its founder, Ron Woznow, became mayor in 2022. Earlier this year, Robin Murray took a temporary leave from the board to manage Conservative MP Aaron Gunn’s Powell River campaign. The group’s current president, Rick Craig, is a retired law educator and also serves as president of the North Lake Association on the lower coast, where he has a lakeside property.1

In response to BC Housing’s proposed projects, the society put together a supportive housing subcommittee.

At first glance, it appears to support supportive housing – an interpretation their spokesperson, Sherry Burton, encourages – never missing a chance to mention how her group “ardently supports shelters, housing and programs for individuals experiencing adversity.”

But, in practice, they do the opposite. They have been laser-focused on the singular goal of excluding drug users from the community and restricting their access to shelter. Their vision of community is one where poverty and addiction are eradicated, not through support and care, but by the sheer force of collective intolerance. As Burton says, “we have already experienced six years of housing-first, and that is not working for the community.”

This summer, they presented their demands to city council. Their first was that the terms of the lease between the city and the shelter operator “must protect the community.”

Who is, and who isn’t, a part of the community wasn’t elaborated.

They went on to request that the shelter be drug-free and its overdose prevention site removed - even though seventy-two percent of homeless people in the region report struggles with addiction. Finally, without concern for winter approaching, they “urge council to postpone permits until community concerns are prioritized and addressed.”

A week later, Burton was at a qathet Regional Hospital board meeting.

A retired paralegal, Burton brought with her a copy of the lease agreement between the hospital and BC Housing (who finance Lift’s supportive housing building on Joyce). In a vaguely threatening legalese, she drew the board’s attention to the Terms of Instrument, section 7.1, which states “the Tenant will not bring onto the Leased Area or suffer or permit to be brought onto the Leased Area any Hazardous Substance.”

She continued,

“Activities such as smoking or inhaling hazardous substances, drug and sex trafficking, theft and coercion, are occurring on the leased premises. These activities are not only illegal, they fall outside the lease’s permitted uses and directly violate its nuisance and hazardous substances provision… We urge the Hospital Board, as Landlord, to ensure compliance with the Terms of Instrument.”

Or, in other words, kick out the crackheads.

The ratepayers want drug users to go away; they threaten businesses, make people feel unsafe, and bring down property values. Seniors are afraid to leave their homes. The stakes are high, and emotions are too. One curious resident who attended the ratepayers’ general meeting in February was so rattled by what he saw that he wrote an op-ed in the local paper, saying that:

“Rarely have I been in a room with such a collection of disgruntled, angry and unhappy people. Most of the animus in the room was directed at four city councillors, with Lift Community Services a close second. The personal animosity held toward these two groups surprised and disturbed me.”

I attended a meeting in September, and the vibe I picked up was fear. Fear of what’s happening to the town they care about. Which is fair. Things are pretty bad, and people should be upset. The problem is, the ratepayers don’t have an explanation for what’s causing the problem.

They’re quick to blame city council, supportive housing management, or harm reduction programs. But they ignore the fact that these problems aren’t only happening in Powell River, or even the province; that homelessness is a crisis across the country with roots that sink deep into our past.

Conspicuously absent from their list of culprits are the ratepayers themselves - the property owners and landlords who have been making an absolute killing off the skyrocketing costs of rent, land, and housing.

PART TWO

The last time British Columbia saw a homeless crisis this bad was during the Great Depression. Things got pretty bleak. Unemployment went as high as thirty-one percent, and homeless camps – or “hobo jungles” as they called them – cropped up in towns across the province. There were an estimated twelve thousand homeless people in Vancouver alone.

The cities of Burnaby and North Vancouver were forced to declare bankruptcy, declaring “the situation in Vancouver is beyond our control.” Small towns were hit, too. The mayor of Kamloops wrote to the Province, saying his “town is being overrun by beggars and panhandlers.”

The provincial government at the time, headed by Simon Fraser Tolmie, believed in small government and applying “business principles to the business of government.” So, instead of raising taxes to lift people out of poverty, they turned the police on the problem. Hobos were picked up and charged with vagrancy. Homeless camps were evicted, cleared, and burnt to the ground.

Leo Olsen, namesake of the Olsen Valley off Powell Lake, remembers the harassment he faced while tramping around, looking for work during the Great Depression:2

“Every time we came to a town, the police tried to get rid of us as quickly as possible. The town police were pretty nasty with the hobos. Anyone brought before a magistrate had to empty out their pockets. Whatever money they had on them had to be handed over. The magistrate would then declare this pocket change a “fine”. Consequently, as we now had no money, we were charged with vagrancy!”

Back then, there was no welfare, healthcare, employment insurance, public pension, or social housing. Employers cut the average wage in half, unions were illegal, and workers were regularly fired without cause. It was clear that the government existed to serve the interests of property and business owners, not the working class. As the depression wore on, people increasingly saw capitalism as the problem, and membership in socialist, labour, and communist organisations boomed.

Concerningly for the government, many of the homeless were combat veterans, hardened in the trenches of Europe. The potential for revolution was palpable. As General McNaughton, Commander of the Canadian Army, described it: “in their ragged platoons, here are the prospective members of what Marx called the ‘industrial reserve army, the storm troopers of the revolution.’”

duck lake unemployment relief camp

The jails couldn’t possibly fit all the homeless and would-be revolutionaries.

So, in September of 1931, the Tolmie government set up “relief camps” in remote parts of the province. One was set up on the south end of Duck Lake in Powell River. Access could be easily controlled – since the Union Steamship was the only way in or out of town – making it an ideal spot to sequester some of the more radical hobos.

Conditions in the camps were rough. Men lived in cramped bunkhouses and were paid twenty cents a day for backbreaking labour.3 They built roads, planted trees, and cleared brush. While attendance was technically voluntary, the alternative for most was a jail cell.

As part of the government’s effort to eradicate communism, men in the relief camps were denied their right to vote. Stuart Lambert, of Myrtle Grove Goat Dairy, lived nearby and made friends with some of the men in the camps. He remembers how:

“The men at Duck Lake marched into town to vote. The officials refused to let them vote; however, they soon changed their minds when their leader shouted out, ‘In that case, boys, let’s take the place apart.’”

Still, officials didn’t include the homeless vote in the final count.

Ultimately, trying to suppress radicalism by concentrating hobos in camps probably wasn’t the best strategy. As one old-timer remembers, “in those bunkhouses, there were more men reading Marx, Lenin and Stalin than there were reading girlie magazines.”

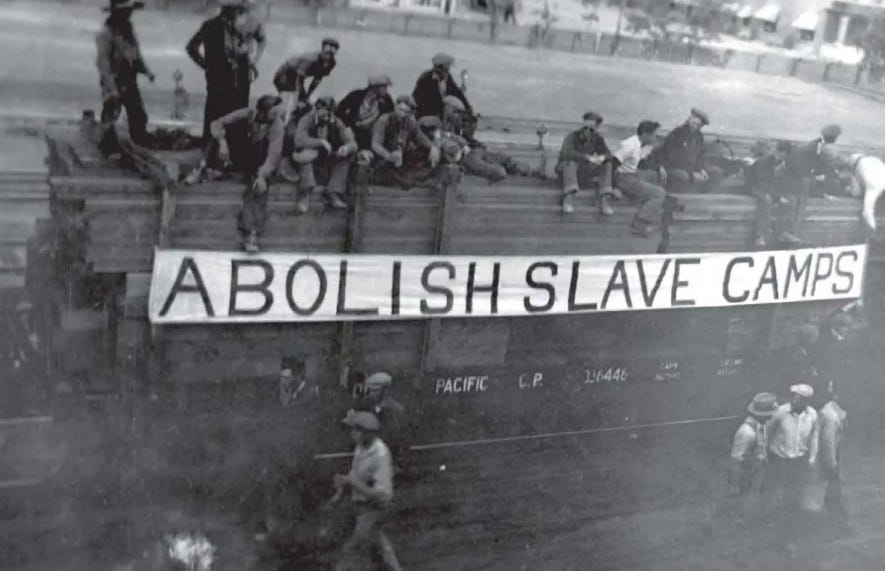

Arthur “Slim” Evans, a carpenter and communist, organised thousands of the campers into the Relief Camp Workers’ Union. In April 1935, they called a general strike. Thousands of homeless men converged in Vancouver and spent several months in protest and riot, eventually culminating in the legendary On to Ottawa Trek and Regina Riot.

Despite popular resistance, the government didn’t budge from its law-and-order approach to poverty. The relief camps ran for eight years, only closing at the outbreak of World War Two.

how was the crisis solved?

After the war, homelessness pretty much disappeared.

The days of pure capitalism and small government were over. To manage the war, the government had expanded massively, and a new post-war consensus emerged. Suddenly, the government was doing previously unimaginable things - introducing heavy regulation, raising taxes, and generally creating a welfare state.

Problems that seemed impossible during the Great Depression were no big deal. The government built thousands of standardized “victory homes” to address the housing shortage; a monthly “baby bonus” was paid to families with children under sixteen; an old-age pension, unemployment insurance, and public healthcare were introduced.

This was possible because rich people paid lots of tax. The marginal tax rate topped out at ninety-four percent; wage theft was a criminal offense; there was an inheritance tax. As a result, the top 1% controlled a modest ten percent of Canada’s wealth.

Over the past few decades, rich people have been chipping away at their chains. Now, the top 1% control nearly a quarter of Canada’s wealth. They got rid of the inheritance tax, brought the top marginal tax rate down to thirty percent, decriminalised wage theft, and stashed billions in tax havens.

The rich got richer.

Meanwhile, the local living wage is $23.3 an hour, and the median wage is only $17.11 an hour. The rest of us don’t have enough money.

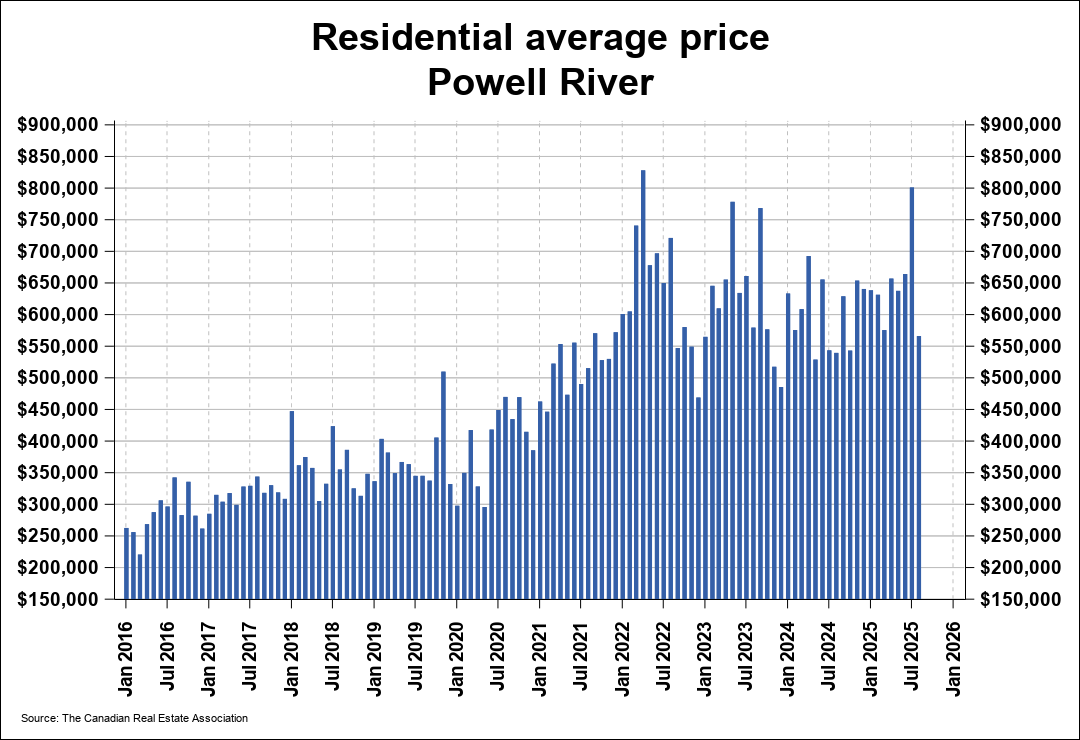

Wealth has concentrated in the hands of property owners. Property values have doubled in a few years, and the net wealth held by homeowners in their principal residences across Canada has grown to $5.8 trillion. For those who own property, it’s been an incredible ride.

Homes have been treated as commodities to be bought and sold, rather than as a basic human need. As a result, there’s no shortage of homes for the wealthy. Powell River “has achieved 5-year and 20-year housing needs for market-rate rental housing and is on track to see sufficient construction of for-purchase homes for above-moderate and high-income households.”

It’s a different story for the young and working-class. We still need a whopping 430 new units of housing by next year to adequately house the very low-income, low-income, and moderate-income households that make up sixty percent of Powell River.

a final word to the ratepayers

"We have ‘sketchy’ people wondering [sic] around at all hours. When we moved here I felt our neighbourhood was perfectly safe. Not anymore. I now avoid certain areas if I’m by myself. This is no longer the neighborhood we moved into.”

- September 2024 letter to mayor and council

I believe the ratepayers are genuine when they say they want to get rid of homelessness and addiction. They’re desperate for a return to the old Powell River.

The trouble is, they aren’t championing any of the things that solved the issue in the past: building public housing, funding social programs, or raising taxes on the rich. Instead, they’re pushing for the lock ‘em up strategy of the Great Depression.

Their understanding of things is all jumbled up.

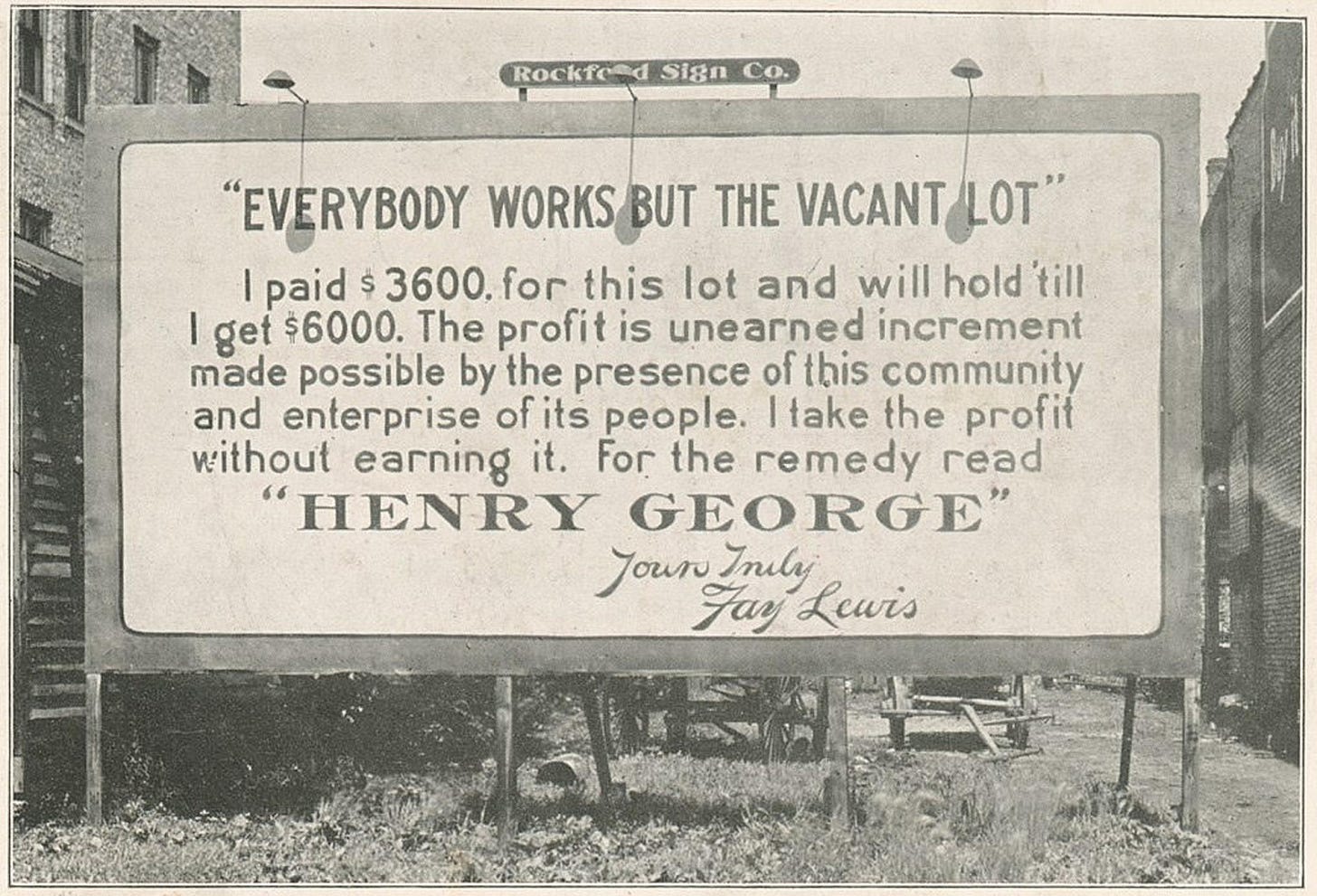

They don’t seem to get that their property value doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s created by, and a measure of, the community’s collective wealth. Prospective homebuyers choose a property based on its neighbourhood and proximity to public goods like schools, libraries, and parks. Location, location, location. Curb appeal doesn’t mean anything if your neighbourhood sucks.

The incredible gains that property owners have seen over the past few years haven’t come out of thin air. They’ve been extracted from the community in the form of rent, stagnant wages, and inflation. The problems we’re facing are the result of rich people taking too much and not contributing enough. If the ratepayers want safe neighbourhoods and high property values, they need to help raise the value of the entire community.

Homelessness and addiction are the symptoms, not causes, of community collapse.

For the diehards who are steeped in the cinematic universe of this blog, I’d also like to note that Craig is a vocal opponent of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA), calling it “one of the biggest issues of this decade,” and inviting PHARA’s spokesperson Sean Mcallister, retired lawyer and yacht owner from Pender Harbour and Area Residents Association to present on the issue.

From Barbra Lambert’s Rusty Nails and Ration Books: Memories of the Great Depression and WWII 1929-1945

four dollars a day, adjusted for inflation

Wow. What a great piece. As a writer/historian, you connect-the-dots with history - i.e. homelessness and the so-called 'Dirty Thirties' to today: the homeless as pawns in local communities. We also have this issue in our community of Courtenay/Comox Valley with government planning a supportive housing and homeless shelter in our very neighbourhood. Organized the neighbourhood last year just to ask questions of BC Housing/City of Courtenay last year: both levels of government/stakeholders stonewalled us. This late summer/fall (2025) conducted a survey of the neighbourhood. The "homeless shelter" is still the number one concern. I, on the other hand, believe the neighbourhood should organized, but look inward and look for ways to improve our neighbourhood (a mixed, low-to-middle income neighbourhood). Not dismiss the homeless/homelessness (we already have a well-maintained/quiet low income apartment complex built, opened by BC Housing in 2019). In closing, your article gave me food for thought and points to consider. Scott, Courtenay, BC.

Thanks for this and the many other great articles!