The Garden City Myth

an open letter to the Townsite Heritage Society

If Powell River has an origin story, it goes something like this:

The city was founded in the early 1900s by Dr. Dwight Brooks, Anson Brooks, and Michael Scanlon (owners of the Powell River Company), who built a uniquely livable community based on the principles of the Garden City Movement.

As the Townsite Heritage Society, a local nonprofit dedicated to historical education and preservation, explains:

“The essential components of the Garden City Movement were grounded in basic respect for the humanity of the individual worker and their family.… Brooks and Scanlon drew from these philosophical movements in the creation of Powell River. The town was preplanned, complete with public gardens and tree-lined streets, all maintained by the Company… The uniqueness and significance of Powell River today can be greatly attributed to the philosophical perspectives of our early cofounders.”

In this telling, the owners of the paper mill are imagined as the city’s founding fathers and generous patrons of the working class.

It’s an image that Brooks and Scanlon cultivated. From its earliest days, the Powell River Company organised an annual garden competition for its employees with prizes ranging from cash to a month’s free rent or vouchers for the company store. At the height of its garden-mania, the company had a whopping fifty-five gardeners on its payroll - a small army responsible for maintaining the company golf course, manicuring executives’ yards, and generally keeping the town immaculate.1

The Townsite Heritage Society has dedicated itself to maintaining this idyllic vision of the town. In 1992, it revived the company’s long-neglected garden competition. In 1995, it petitioned the federal government to recognize the mill and surrounding townsite as a National Historic Site of Canada. In their words:

“We felt we had to save this area of the district from becoming a slum; we owed it to our founders Brooks and Scanlon and their successors, Scanlon nephews, managers Harold and Joe Foley.”

It’s noteworthy that Joe Foley, president of the Powell River Company from 1936-59, left the Society “a very sizable sum” when he died in 2001.2 The same year, the Society bought Henderson House, the first doctor’s residence and one of the oldest buildings in Powell River. After eight years of restoration, it’s now a living museum and the society’s period-accurate headquarters.

The Heritage Society doesn’t stop at organising garden competitions or installing commemorative plaques.

In 2016, Powell River was in a housing crisis. With vacancy rates hovering around one percent, landlords were taking advantage of high demand and jacking up rents, causing the city’s average rent to nearly double in just a few years. Local wages weren’t keeping pace, and a growing number of residents (over two thousand, many of them children and seniors) were classified as low-income by the government census.3

In an attempt to increase the rental supply and lower rents, the city proposed a bylaw amendment to allow carriage homes on private property. The Townsite Heritage Society protested, arguing that “carriage homes are not in keeping with the Garden City Movement that the Townsite was modeled after,” and the “National Historic District designation could be put at risk if carriage houses were permitted within the neighbourhood.”4

As a result of their lobbying, the city granted an exception to Townsite. Even though a majority of the neighbourhood’s lots are big enough to accommodate a carriage house, the new bylaw bans them, denying families rental income and contributing to the issue of housing scarcity in the region.

what was the Garden City Movement?

“The land around Garden City is, fortunately, not in the hands of private individuals: it is in the hands of the people: and is to be administered, not in the supposed interests of the few, but in the real interests of the whole community.”

— Ebenezer Howard, 1898.

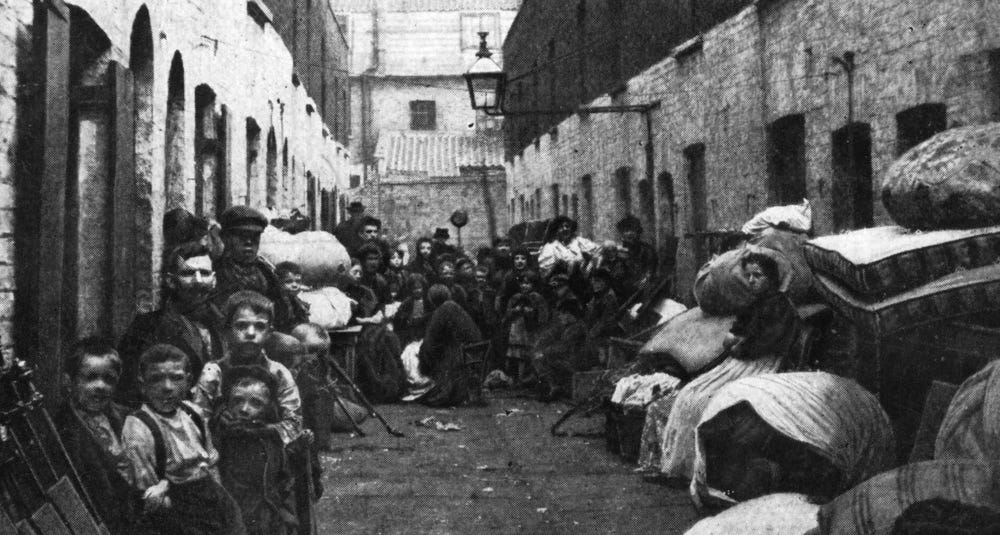

Ironically, the Garden City Movement developed in response to another housing crisis, one that was ravaging London at the turn of the 19th century. A result of the Industrial Revolution, London’s population doubled from three million to over six million in a single generation. Landlords were price-gouging, and the city was a dense tangle of overcrowded slums and homeless encampments.

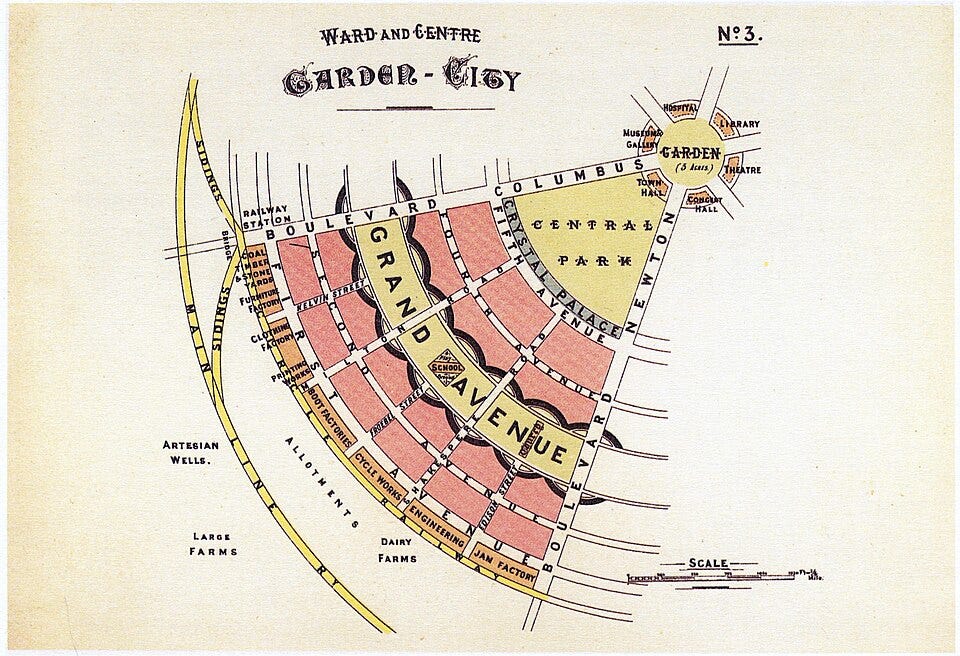

It was in this context that Ebenezer Howard published his 1898 book, Garden Cities of To-morrow, and laid out his vision for a utopian city, free from the squalor of London.

Despite its title, the book doesn’t have much to say about gardens. Only one of its thirteen chapters concerns green space or the ideal layout of a town. The other twelve chapters dive into the weeds of how a Garden City should function in terms of governance, finance, and administration. The book’s original title, To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, gives a better sense of its scope.

Howard cites the English revolutionary Thomas Spence as inspiration for his ideas, although he’s careful to distance himself from Spence’s more radical calls for the abolition of private property (ideas that landed Spence in a London prison for treason a century earlier). Instead, Howard advocates for the “abolition of landlord’s rent,” suggesting that an elected board would replace private landlords, and the profits redistributed for the benefit of the community.

Essentially, his vision was socialist, emphasizing local government and co-operation over private ownership and monopoly.

It makes sense, since Ebenezer’s buds were socialists and anarchists.

Before Howard became known for his Garden Cities, he presented an unfinished manuscript, Common-sense Socialism, at a meeting hosted by the anarchist group, Brotherhood Trust. The Brotherhood was receptive to, and helped refine, Howard’s ideas. They ran two industrial communes, established by blacklisted union workers who transitioned to building bicycles and repairing electrical goods in a worker-owned co-operative.5 According to their newsletter:

“The organisation is entirely Anarchist & Communist in character. Each man receives according to his needs, on the basis of a common agreement, without the aid of any laws or rules. The profits from the business are to be devoted to its extension and ultimately to the establishing of a regular Community Colony – an oasis is the desert of commercialism”

When Howard founded the Garden City Association in 1899, some of its earliest members came from the Brotherhood Trust.

The first Garden City to be built – Letchworth Garden City in 1905 – was designed by Raymond Unwin, an Arts and Crafts architect and member of William Morris’ Socialist League.6 The experimental city was a hotbed of radicalism. Its first residents were recruited from the Brotherhood Trust and the Christian-socialist Labour Church. The city’s newspaper, the Letchworth Gazette, was run by the Independent Labour Party - a newly formed “big tent” leftist party.

Housing reform was at the heart of the Garden City Movement. Aside from their involvement at Letchworth, the Socialist League and the Independent Labour Party organised renters in London’s slums into Tenant Defence Leagues. Rent strikes and direct action were their tactics of choice against exploitative landlords. As the Socialist League’s Commonweal newspaper put it:

“When a black flag bearing the words ‘no rent’ floats over a single slum, when streets are torn up and barricaded, when from the windows and roofs of the houses there comes a shower of hot water and storm of stones and brickbats, what can the police or bailiffs do?”

who were Brooks, Brooks, and Scanlon?

Knowing what the Garden City Movement was, it’s hard to take the Townsite Heritage Society’s claims seriously.

As I’ve written about before, Brooks and Scanlon were union-busting businessmen, hostile to the labour movement and opposed to anything that resembled socialism. A more accurate description of them would be: wealthy Gilded Age lumber barons who were expanding their empire westward after having decimated the boreal forests of their native Minnesota.

In 1899, a year after Garden Cities of To-morrow was published, the Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company built the largest sawmill in existence in Cass Lake, Minnesota. Producing over 115 million board feet of lumber per year, within a decade it had “completely exhausted the supply of standing timber” and was abandoned.7

Flush with cash, the company started expanding across the continent. They ran their mills around the clock, three shifts a day, cutting over 1.3 billion board feet of longleaf pine in one Louisiana mill alone. By 1920, they were the largest landowner in Florida. They owned railroads, lumberyards, mills, power plants, and a shipping company. They had holdings in Minnesota, Texas, Louisiana, Florida, Cuba, the Bahamas, California, Oregon, and British Columbia.8

Despite their local image as founding fathers, neither Brooks, Brooks, nor Scanlon ever lived in Powell River. The pulp and paper mill was only a small part of an international empire that they managed from their headquarters in Minneapolis. Still, they exerted an incredible amount of control over the daily lives of the town’s early residents.

They owned every building in Townsite and deducted rent and groceries from their employees’ paycheques. Shifts at the mill were long, and Sundays were the only day off. If anyone asked for an eight-hour day, better pay, or other communist things, they were watched closely. Many ended up fired, blacklisted, and evicted from their homes.

Merve Wilkinson worked at the mill in those early days. Later in life, he was recognized by the Order of Canada for his pioneering work in sustainable forestry. His biography is an incredible source of insight into early life at the Powell River Company:

“Every department had a private detective hired to keep track of possible labour unrest. They were supposed to be deep undercover, but they all came from the same detective agency and usually wore the same sort of clothes. The men spotted them quickly and made a game of feeding them false information. If someone were a real company man - a ‘suckhole” as he was called - the men would tell the detective about him, “Hey, you’d better watch that one. I think he’s a communist.”

The company’s biggest beef was with the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) - a socialist party that openly boasted of its goal to eradicate capitalism.9

As Jack Dice, a mill worker during the Great Depression, tells it:

The mill manager, Joe Falconer, had his orders to fire anybody suspected of belonging to the CCF. All that was needed to get someone fired was to tell Joe that a certain employee was CCF. Joe then removed that employee’s punch timecard; this action informed the employee he was fired. The employee was not only fired by the Powell River Company but he was blacklisted by all other companies, throughout Canada…

Met an electrician that had been fired recently by the Powell River company. His story was that after his last shift he had been called into the office of Dick Woodruff, assistant super. He was asked to take a promotion to Mr. Hanson’s job. His answer was that if he accepted the job, he would be accused of turning in Mr. Hanson as a CCF member so he turned down the promotion. When he went to work the next day, his punch timecard had been pulled. He had been fired and blacklisted for turning down a promotion!10

The atmosphere of fear and reprisal was ripe for abuse:

The superintendent didn’t much care about anything other than having the men working at breakneck speed. He also had the rather nasty habit of calling around at a new man’s home while he was working and telling the wife that her man would be out of a job unless she was very nice to him. His nickname was “Papa.”

When Merve first heard it, he couldn’t figure it out.

“Why do you call him Papa?” He asked one of the men. “He’s one of the most unlovable men I’ve ever met.”

“You’ve got the wrong end of the handle,” the man said, “we call him Papa because he’s got so many illegitimate children in town.”

Despite the company’s efforts, Powell River workers elected the CCF to the provincial legislature in eight out of ten elections between 1933 and 1966.11 Decades of agitation paid off. By 1973, 2,233 of the mill’s 2,600 workers were unionised, and the oppressive days of Brooks and Scanlon were all but forgotten.

Scanlon’s ghost, or, why I’m dunking on some sweet old timers

“The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make.”

— William Morris

I’m writing this with respect for the Townsite Heritage Society and its members, who are my fellow local history nerds. It might seem trivial, and no doubt it’s a silly fight to pick, but the Garden City myth isn’t just harmless nostalgia.

How we remember Brooks and Scanlon matters. Income inequality is at an all-time high, historic labour gains are being stripped away, and the housing crisis shows no signs of slowing. How we understand our past informs how we will respond to the present.

Thanks to a generous inheritance from Michael Scanlon’s nephew, the Townsite Heritage Society has an outsized role to play in setting the terms of our collective memory. By choosing to obscure the true legacy of the mill and its founders, the Society is distorting our understanding of who we are.

Things improved, not because Brooks and Scanlon were great guys, but because workers and tenants fought back against their greed. That’s the lesson of the Garden City Movement, and that’s the legacy of the Powell River Company.

Storytelling in the Fourth World: Explorations in Meaning of Place and Tla'amin Resistance to Dispossession. Lyana Marie Patrick. 1997.

House Histories and Heritage Vol. I. Karen Southern (founder and former president of Townsite Heritage Society). Co-written by Mark Cooper, grandson of Russell Cooper, the Powell River Company’s last resident manager. He writes:

“From today's perspective, it seems fortuitous that Brooks and Scanlon were drawn to the humanistic precepts of the Garden City Movement before they began construction of the Powell River Company town in 1911… one of the significant recommendations of the Garden City Movement was that a substantial amount of the profits was to be returned to the community. While this recommendation has not been verified at this time in the case of Powell River, it is true that a great deal of money had been channeled into the construction of quality buildings and residences.” lol

Housing Need & Demand Study 2018. City of Powell River

SOCP and Zoning Bylaw Amendments - Carriage House Regulations. December 13, 2022. City of Powell River

The radical roots of Garden Cities. Quintin Bradley. 2015.

The Arts and Crafts Movement is another socialist movement the Townsite Heritage Society attributes to Scanlon and Brooks, but lets not get into that

Scanlon Mill Closes The Virginia Enterprise. Aug 13, 1909, Page 8

Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company Wikipedia

Regina Manifesto 1933

Rusty Nails & Ration Books. Barbara Lambert. 2002 (an incredible primary source for local workers’ experiences during the Great Depression)

Thanks for this really valuable historical myth-busting!

Can you say how large the lots in Townsite are in general?